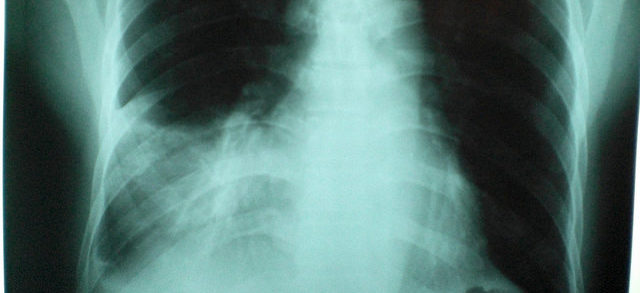

Keeping Our Bones Strong As We Age

By Meredith Kimple How many of us were encouraged to drink a glass of milk every day when we were children? The importance of strong bones is drilled into our heads from an early age, but the effects of an inadequate calcium intake are not obvious […]

Read More